The UK government is eagerly anticipating the arrival of self-driving cars. Predictions thus far have been optimistic: in 2017 the then UK Chancellor, Philip Hammond, promised that driverless cars would be on our roads by 2021. This has not come to pass anywhere in the world outside of carefully mapped testing sites. In 2018, the government passed the Automated and Electric Vehicles Act (AEV) 2018, with the goal of placing the UK at the forefront of the electric and autonomous vehicle revolution. The Act sets out the insurance regime for autonomous vehicles and empowers the government to encourage and direct the proliferation of electric charging stations, in pursuit of its promise of net zero emissions from all cars sold from 2035. Then, in January 2022, the Law Commission published its report on how the law should change in response to the introduction of automated vehicles, making a number of recommendations that will be laid before Parliament in 2022.[1]

While UK law under the AEV Act accommodates for driverless cars to be road-legal, the authorisation scheme has yet to authorise any “self-driving” cars. In January 2021, a regulation approving the authorisation of automatic lane keeping systems (ALKS) came into effect. Designed for use on a motorway in slow traffic, ALKS enables a vehicle to drive itself in a single lane, while maintaining the ability to return control to the driver when required. Systems such as Tesla’s Autopilot have been keeping cars in lane on British roads for some years – and at speeds far higher than the 60km/h envisaged in the new regulations – however, under the previous law, drivers were technically required keep their hands on the wheel and their eyes on the road. The Department for Transport said ALKS would be the first form of hands-free driving legalised in the UK. ALKS represents the first step in testing autonomous vehicles on UK roads, but it falls short of the bold claims made by companies and politicians for the decade ahead. How far away are we from the reality of legal self-driving cars, asks Claire Gerrand, Consultant, D2 Legal Technology (D2LT)?

False Perceptions

If you were judging by the Tesla website, you may think that self-driving cars are already being sold in the UK – after all, Tesla sells software for its electric cars under the brand names ‘full self-driving’ and ‘autopilot’. Autopilot instead refers to a suite of driver assistance features including cruise control, auto lane change, auto-park and “smart summon”, where the car drives itself to you in a parking lot. Upgrading from ‘autopilot’ to ‘full self-driving’ gives you traffic light recognition, with the promise of an ‘autosteer’ feature on city streets marketed as ‘upcoming’ at an unspecified time. These labels contribute to a false perception of the abilities of these cars – an MIT survey found that 23% of people believe fully autonomous, driverless cars are being sold to consumers today.

To combat this perception, the Law Commission recommended that advertising unauthorised cars as ‘full self-driving’ should be a criminal offence because it risks confusing drivers as to whether they must pay attention to the road. Similar complaints have been directed at the government by insurers for its misleading announcement of the legal approval of ‘self-driving’ cars, that were, in fact, simply ALKS.

Tesla drivers have in recent years become notorious for distracted driving – US safety regulators have opened 30 investigations into crashes, involving 10 deaths, since 2016 where Tesla driver-assisted technology was in use. These drivers have been found to have been watching TV, sleeping while travelling at 150km/h, playing video games and sitting in the passenger seat. Tesla’s operating instructions for ‘full self-driving’ supposedly requires drivers to keep their hands on the wheel at all times, allowing it to circumvent certain regulatory schemes and market the software as a driver-assistance system. In reality, the climbing incident rate has made Tesla drivers infamous for circumventing this requirement, with Tesla’s CEO, Elon Musk, demonstrating hands-free driving himself in interviews[2].

Commercial Availability

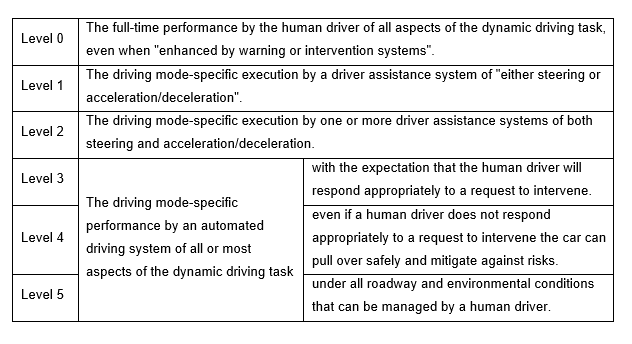

Companies in this space have thus far overpromised and underdelivered. Tesla, GM and Lyft all promised to roll out fleets of robotaxis by 2020/2021 but failed to do so – a 2020 AAA study found that vehicles equipped with active driving assistance systems experienced some type of issue on the average of every 8 miles in real-world driving[3]. Unlike Tesla’s strategy of beta-testing its new features on volunteer Tesla owners (a privilege costing drivers $12,000 up-front or $199 per month), some of the more promising tech companies have limited their cars’ scope in order to perfect its technology. Waymo (owned by Google’s parent company Alphabet) operates self-driving robotaxis without back-up drivers in the front seat across four carefully mapped suburbs in Phoenix, Arizona. This is considered Level 4 automation – it can drive without a human operator, but it cannot properly accommodate for flawed mapping and adverse conditions like rain. While Level 4 is the most advanced model on the road, the idea of going off-grid in Waymo’s taxi is years away. The most advanced self-driving vehicle a regular consumer can buy is likely the 2021 Honda smart hybrid car, which is capable of driving, switching lanes and passing vehicles on freeways, and encourages you to go hands-free with their Traffic Jam Pilot. Honda says drivers do not have to pay attention to the road until they’re prompted to do so by the car. But when drivers are prompted, they must be ready to take back control immediately or it will eventually slow and stop the car after multiple alerts. This is an example of Level 3 automation: the car drives itself with the expectation that a human driver will step in almost immediately if requested. True Level 5 – the ability to operate in any and all road conditions where humans can, without a human driver – does not yet exist. A thinktank’s report from March 2022 estimated that Level 5 autonomous vehicles may be commercially available and legal to use in some jurisdictions by the late 2020s, but will initially have high costs and limited performance and range.[4]

SAE (2019) J3016 Levels of Automated Driving, Link.

The first self-driving cars will most likely be electric. Research from the University of Michigan estimates that the energy required for the computational demands of these intelligent systems will outstrip the capacity of current electric cars. Energy savings will be made elsewhere; where all cars on the road are autonomous, it will cut down on the average 45 hours in traffic annually that drivers face. More importantly, the University of California estimates that each robotaxis could remove 9 – 13 conventional vehicles from the road and cut down on the average vehicles’ lifetime spent unused (more than 90%)[5]. Nonetheless, even before robotaxis become ubiquitous and traffic is eliminated, its estimated that cars with automated acceleration and braking (a technology on the roads today) can reduce fuel consumption by more than 15%[6]. The transition to an electric and (at least, partially) autonomous fleet of cars may prove necessary if the UK is to reach net zero emissions by 2050.

Driver Re-Training

The real test for self-driving cars will be whether they make our roads safer. The Law Commission’s public consultation found that a positive risk balance was seen as the minimum acceptable standard: overall, automated driving should cause fewer deaths and injuries than human drivers. Driver complacency is typically the cause of incidents related to automated technology in Level 3 vehicles and below. Beyond Level 3, the car will operate without human intervention, although it may request that a driver takes control if it encounters an unexpected situation. For contrast, confidence in fully-automated technology plummeted after Boeing’s 2018 and 2019 737 Max plane crashes: the pilots were not trained or properly informed by Boeing on how to handle the stabilising software. A single failed sensor caused the planes to erroneously employ pilot-assistance technology that caused the planes to nose-dive towards the ground and crash. Pilot Sullenberger, best known for landing in the Hudson, noted in a 2021 interview that, “it requires much more training and experience, not less, to fly highly automated planes.”[7] Driving Level 3 and 4 automated cars, much like flying planes, may require drivers to re-train. For now, proposed laws will still require ‘users in charge’ of driver-assisted and automated cars to hold driver’s licenses, but once Level 5 automation is in common use, it would quickly become redundant. Once steering wheels are removed (as predicted by GM and Tesla) it will become impossible for human drivers to intervene, creating an entirely new legal landscape as envisioned by the Law Commission.

Changes in UK Law

The driver or ‘user-in-charge’ in an autonomous vehicle currently faces the same legal accountability that a regular driver faces. Under the Law Commission’s proposal, if an autonomous driving feature causes the vehicle to drive in a way which would be criminal if performed by a human driver, it would be dealt with as a regulatory matter. The ‘driver’ of the autonomous vehicle would have immunity from a wide range of offences related to the way the vehicle drives, from dangerous or careless driving, to exceeding the speed limit or running a red light. However, the Law Commission is not envisioning a completely hands-free experience – the driver may be required to take over driving in response to a “transition demand”, given sufficient notice, if the vehicle encounters a problem it cannot handle. The report is sceptical of the ability of passengers to be constantly alert in these cars, given that increased use will only lead to complacency. Musk echoed this observation in 2018, stating that “when there is a serious accident it is almost always the case that it is an experienced user, and the issue is more one of complacency”. To be road-legal under these proposals, in the event the ‘user-in-charge’ fails to take control, the car must be able to mitigate against any unforeseen problems, by slowing down and moving to a safe harbour. The responsibility for dangerous driving or faulty software ultimately falls to the manufacturer/developer, where an emphasis will be placed on ensuring the safety of future iterations of the vehicle’s design.

However, simply because there are no automatic criminal penalties for the company if one of their cars drives dangerously, does not mean that there is no legal consequence resulting from a car accident. The Law Commission suggested that the manufacturer should face regulatory fines and intense scrutiny. Manufacturers should attract criminal liability if they were found to misrepresent the car’s abilities or fail to disclose suspected faults or features in its programming. Victims of car accidents should be compensated by an insurer (the driver’s or the company’s, depending on the direction of legislation) under the Automated and Electric Vehicles Act 2018. The ’user-in-charge’ of the car would be required to fulfil other driver duties, such as arranging compulsory insurance, using seatbelts and checking loads. While we’re years away from driverless cars, the necessary legal foundations are on their way. A 2020 KPMG report ranked the UK ninth in terms of overall readiness for autonomous vehicles, with the UK earning second place behind Singapore on the Policy and Legislation pillar.

Conclusion

Self-driving cars have the ability to revolutionise our transport system. It could eliminate the estimated 94% of accidents resulting from human error; not to mention the savings in time and labour involved in transport across all industries. We should expect there to be bumps along the long road ahead, as competition in innovation can lead companies to run greater risks in the search of increased performance. The legal landscape surrounding self-driving cars is far from fully defined, and it has proved especially difficult to account for the ‘edge cases’ that arise in Level 3 or 4 cars. The question of who holds legal responsibility for a self-driving car will be answered by Parliament in the coming years – and whatever the result, it is unlikely to hamper the £41.7 billion[8] race to be the first company to put a self-driving car on UK roads.

[1] Law Commission. (26 January 2022) Automated Vehicles. Link.

[2] McPherson, J. (2022). “In His 60 Minutes Appearance, Elon Musk Was Not On The Level(s)”, Link.

[3] AAA – The Auto Club Group. (2020). Study: Driving Tech Fails Every 8 Miles. Link.

[4] Litman, Todd. (3 March 2022). Autonomous Vehicle Implementation Predictions. Victoria Transport Policy Institute. Link.

[5] ‘Life Cycle Assessment of Connected and Automated Vehicles: Sensing and Computing Subsystem and Vehicle Level Effects’ – Environmental Science & Technology 2018 52 (5), 3249-3256. Link.

[6] Austin Brown, Brittany Repac, Jeff Gonder. Autonomous Vehicles Have a Wide Range of Possible Energy Impacts. United States: N. p., 2013. Web. Link.

[7] Malmquist, S., & Rapoport, R. (2021). The Plane Paradox: More Automation Should Mean More Training – Aviation Training & Consulting EN. Link.

[8] Department for Transport and Centre for Connected and Autonomous Vehicles, “Connected Places Catapult: market forecast for connected and autonomous vehicles” report. 13 January 2021. Link.